What It Feels Like to Compete at the Biggest Ice Swimming Race in North America

)

Its a Saturday morning in late February, and OConnor, 51, who serves as safety director for the annual Memphremagog Winter Swim Festival, is holding a quick briefing inside the East Side Restaurant and Pub, a tavern that doubles as a staging area just a few hundred feet from the competition zone.

As basically the only subzero meet in North America, the Winter Swim Fest is free to make its own rules. The frigid pool is limited to two lanes and 25 meters. Races range from 25 to 200 meters and include the classic swim-meet strokes of freestyle and butterfly and various relays. While parka-clad volunteers clock times, competitors race attire must be chillingly confined to English Channel rules: just a cap, goggles, and a standard swimsuit.

This setup means no flip turns. (If you turn wrong, you end up under the ice, OConnor says.) No holding the ladder or the wall too long at the end. (It gets icy, and your hand can freeze to it.) And no matter what, you need to stay in touch with how youre feeling. (You can go downhill really fast.) The popularity of ice swimming has spiked in recent years, so about half the field at Winter Swim Fest is new. If you dont have anxiety, OConnor clarifies, it means you have no idea what youre getting yourself into.

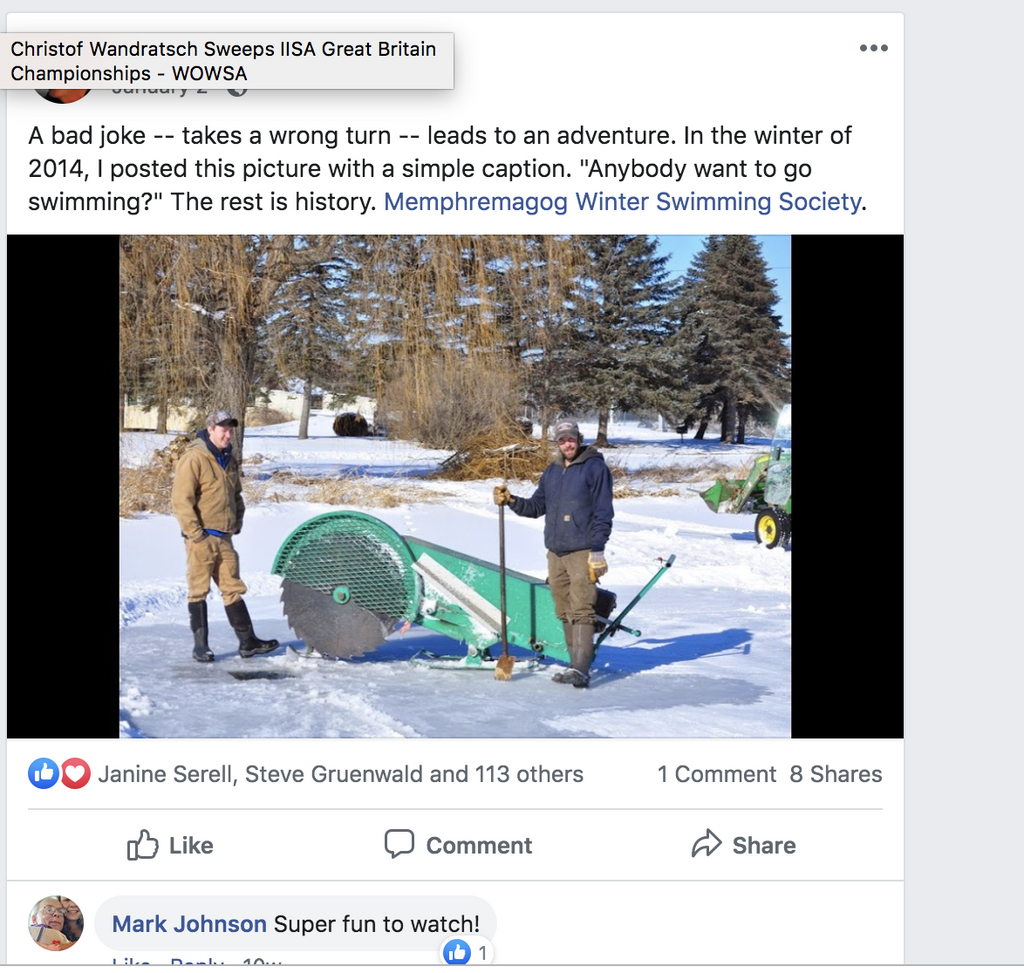

It all started out as a half-joke deep in the winter of 2014. Race director Phil White, then in his mid-60s, posted a photo of himself on Facebook standing on the ice of Lake Memphremagog with a three-foot circular saw and the now-infamous phrase Anybody want to go for a swim? Then Darren Miller, a marathon swimmer and race organizer in Pittsburgh, saw the post and called to ask, Are you serious? One year later, 40 hardy swimmers turned up for the first event, and over the next half decade participation doubled with little obvious reward at stake.

Bragging rights and pool records aside, the top finishers receive little more than Vermont maple syrup and a lot of homemade beef jerky (for first place), or a little less beef jerky (for second), which hints that there must be some stronger pull below the surface. After the briefing, several swimmers around me chatter nervously about how maybe this whole thing wasnt such a good idea. I can empathize. Im a devoted warm-water marathon swimmer and cant get my head around the draw. So Ive signed up to participate in the 25-meter breaststroke. In less than five hours, I too will be forcing myself into the frigid water.

THE WINTER SWIM Festival always kicks off with the hat competition, a true icebreaker of an event: a 25-meter head-up breaststroke thats judged not on your speed but on your hat alone. Its a showcase of creativity and engineering, with some headgear accessorized by lights and waterproof speakers.

Among this stream of contestants now heading toward the water, Derek Tucker, 49, stands out for wearing a bright pink papier-mch pig hat so voluminous you could probably see it from space. He and his kids designed it together, he explains, regarding it with a mixture of pride and trepidation. Hes fully aware that hes broken the classic nothing new on race day rule by not test-captaining The Hat beforehand. Despite being an ultraswimmer and ultrarunner, hes not sure he can actually keep his head above water while wearing it. Worst case, Ill just tread water and scull, he says, shortly before descending into the pool.

Once exposed, Tucker and I descend some wooden steps on either side of the pool and stand on a submerged platform that runs between them. We take one second to fist-bump, then grab the ice-crusted rail behind us in a set position. Someone shouts Go, and were off. The adrenaline of the moment takes over, and within a few strokes Im able to duck my head under the water. My 25-meter race takes all of 25.97 secondsand even though Tucker beats me to the far wall, I arrive there tingling, ecstatic, and can't stop grinning.

Whether youve finished or pulled out early, volunteers at the end of the lane do the same thing, heat after heat, swimmer after swimmer: Bundle, aid, congratulate. The hallmark of this festival, as much as it is the ice pool itself, is the wrapthe move a volunteer does with a towel or giant robe to bundle the swimmer back up when they emerge from the water, skin varying in shades from ruddy to full-on lobster. Now its my turn to feel it, as the volunteers make sure my frozen feet get into my shoes and that my robe is zipped.

Earlier, I spoke with one of the fast, young up-and-comers in the sport, the Dutch athlete Fergil Hesterman, 28, who described the ice-swimming community as one big family that helps each other out. Its easy to feel what he means.

MY TIME IN the breaststroke placed me solidly midpacktenth place out of 21 womenand yet I still spent the rest of that day feeling victorious. Id tapped into the mind-over-matter part of the sport, which is incredibly satisfying.

Perhaps no one embodies that ideal more than CIBBOWS swimmer Seth Bornstein, who is attending his fifth festival and has recently returned from the international championships in Bled. When we meet, one of the first things he tells me is Im the slowest swimmer on world record. Thats verified. He still swims regularly. I realized that I know I can do this; I dont have anything to prove to anyone anymore, especially myself.

Bornstein, 63, swam in the hat competition, sporting a stuffed turtle atop his cap. It went well, he says, but he decided to scratch his 25 freestyle scheduled for later in the day. For him, its not about fast times or specific distances; its about just being among the field. I didnt grow up athletic, he says. I was born with cerebral palsy and I wore a leg brace as a kid. I never thought I could do physical stuff. Those who have known me for a long time are kind of happy. They know its something I wantedto be athletic. It took me 50 years to get to that point. Its fun.

Toward the end of the day, more names get crossed out, more people are re-paired up, and in Memphremagog festival style, everyone rolls with it. By dinnertime, its like one big Christmas night, people strolling around in their pajamas (wear your PJs, get one free shot of vodka from the bar) and feeling the effects of adrenaline fatigue, pride, and whatever you call the feeling that comes from being with people who totally get you. People whove watched you shiver, dare, fail, and do things you never thought youd do, again and again.

When the sun rises the next day, the outside temperature remains low, with a real feel of nearly zero. Thats lucky, in a way, because its an inconvenient time for ice swimmings popularity to be surging. Warmer weather caused the water at the recent British Ice Swimming Championships to hit a balmy 43.5 degreestoo warm to be considered an ice swim, so no records could be officially counted. At least one extremist, Lewis Pugh, a British-South African endurance swimmer and activist, is embracing that sad fact by doing ever more dramatic swims in places you wouldnt think humans could flutter-kick, like the North Pole and, recently, a tunnel of melting ice in east Antarctica, to bring attention to global warming.

The second days races go much like the firsts, except for the final event, a set of spirited relays that are as much about whats happening on the deck as in the water. Theres a flurry of activity as swimmers and volunteers race around to coordinate just whos about to go into the water, and how to make sure everyone exiting the pool is wrapped and cared for. Its a game of timing and positioning, frequently messed up, always forgiven, with choruses of Sorry! Sorry! and Go! Go! mingling in the air while volunteers shuffle dry, warm clothes around on deck to get them to the right swimmer at the right moment.

Relays are supposed to be pod against pod, except theyre kind of not. Cheers erupt everywherefor your team, the other team, the volunteers around the pool. And I find that Im cheering for everyone else, too. Its all, as Tucker once warned me, so silly and unnecessary, and yet energizing and fun and empowering to watch. I think the sport is growing because it connects us to a real feeling of being alive, says Margaret Gadzic, 41, a soft-spoken swimmer and organizer on the Buckeye Bluetits. This is something you can do to feel your breath catch, your heart race, and your blood pump in your veins.

Once the commotion finally stopped, the ice returned, and barely 24 hours later the pool sealed over. You could say that nothing lasts forever. But theres always someone willing to crack another spot open.

)

)

)

)

)